“There’s always something,” announces the 22-year-old black midi bandleader Geordie Greep on the opening title track of their new album, Hellfire. His thick British accent is surrounded by a tidal wave of intense instrumentation — including, but not limited to, cello, violin, accordion, lap steel, whistle and mandolin. “An odd twitch, hearing loss/A ringing noise, new flesh/A new bump, a weightlessness,” he spits in a rapid-fire list that goes on and on.

black midi — consisting of Greep on vocals and guitar, 22-year-old Cameron Picton on bass and vocals and 23-year-old Morgan Simpson on drums — are a genreless group that most often get dubbed as post-punk, which might be a curse for every off-kilter act that’s native to the U.K. They’ve been interested in this sentiment of a singular disturbance, this one twitch or bump, since their inception, and blowing it up. Their agitated 2019 debut Schlagenheim received praise for its restlessness, especially in a time where their peers — Fontaines D.C., Preoccupations, Iceage, Squid — don’t quite come close to the idiosyncrasy that black midi encompass.

Off the bat, Schlagenheim catapults its listener outside of their comfort zone with the five-minute “953” and makes them question what they enjoy sonically. It lacks melody and sense; it moves freely, interspersed with piercing static and brooding pauses. The entire album zones in on that tiny inch and makes it gigantic. At times, the songs feel almost religious, with repeated refrains that resemble hymns, or by grappling with existential ideas like on “bmbmbm”: “And she moves with a purpose/And she moves with a purpose/With a purpose, it is so magnificent,” Greep murmurs sardonically.

This eclectic palette and holy reckoning can be traced back to their childhoods. “The area I grew up in, Walthamstow, is quite a culturally diverse area, which is obviously brilliant for a young person,” Greep explains over Zoom in late June, sitting at a desk in a room with white walls and a closet whose door is completely open, revealing an array of monotone button-down shirts. When he was around 11 or 12, he was invited by a friend a few years older to play music at a church. “He said, ‘Get involved,’ and I just started going there most weekends, going to events and concerts out in the middle of Reading. It was good fun; it’s a brilliant experience for any musician.”

As he’s sharing this story, Simpson pops into the meeting, seemingly during golden hour because sunlight pours over him and the white walls of his room. He had a similar experience to Greep growing up, though it was in a more traditional sense. Christianity is a major part of his lineage, so much so that his sister is training to become a vicar. Up until he was around 14, he’d go to church every Sunday. His family is also very musical: “My dad plays guitar and bass, my mom sings, my sister plays, my uncle plays, my godfather plays,” he says. “One service after church, people were having their teas and coffees. There were drums, and they saw my uncle Robert was at them. Everyone walked around, and I was on his lap playing, and he was controlling the feet.”

He adds, “I say that because without being immersed in such a musical environment, I don’t think I would have played so early and also developed such a passion for what I do.”

The three of them met at the BRIT School in London, which, according to the band’s biography, often gets overplayed in their story. It is a prestigious institution, especially for those studying performing arts, and it aided them in profound ways. “Everyone was doing their own thing; everyone had their own individual tastes,” Picton says, shortly after joining the Zoom and admitting that he thought he had two more hours until the interview. He’s at a bar after going to The National Gallery with some friends, his voice mingling with background chatter and the blaring of indecipherable music. “It was such a great learning environment, especially at that age to get to play with so many people. We were really lucky to have the year group we had, as well as two of the teachers in particular who were really excellent and passionate. They really encouraged us to go down the rabbit holes they went down with music. We’ve seen them come to our shows.”

Schlagenheim immediately earned them respect. Their improvisational technique amused critics, and obviously satisfied fans; the spontaneous and organic nature of the songs was part of what made them so groundbreaking. The catharsis that arrives is not at all planned. It unravels gradually as the members jam out together with a tape recorder in the room. After the sessions, they would listen back to it, point out the special moments and refine them. It helped capture the electric energy of their live shows.

Receiving due praise set the group on a high pedestal. And then their 2021 masterwork Cavalcade proved that they weren’t temporary. It leaned into their theatrical, witty side, with Greep acting as a narrator in a play and the instrumentation more orchestral and alive than ever. Simpson describes it as “a broader, wider, more colorful palette of sounds compared to Schlagenheim,” he says, calling the debut “claustrophobic.” “The first record was material that we had been paying for a year-and-a-half as a band. When that music is so under your fingers to that extent, it’s almost hard to unlearn or untrain yourself when you get to the studio setting to keep it a bit fresher or add a bit of life.”

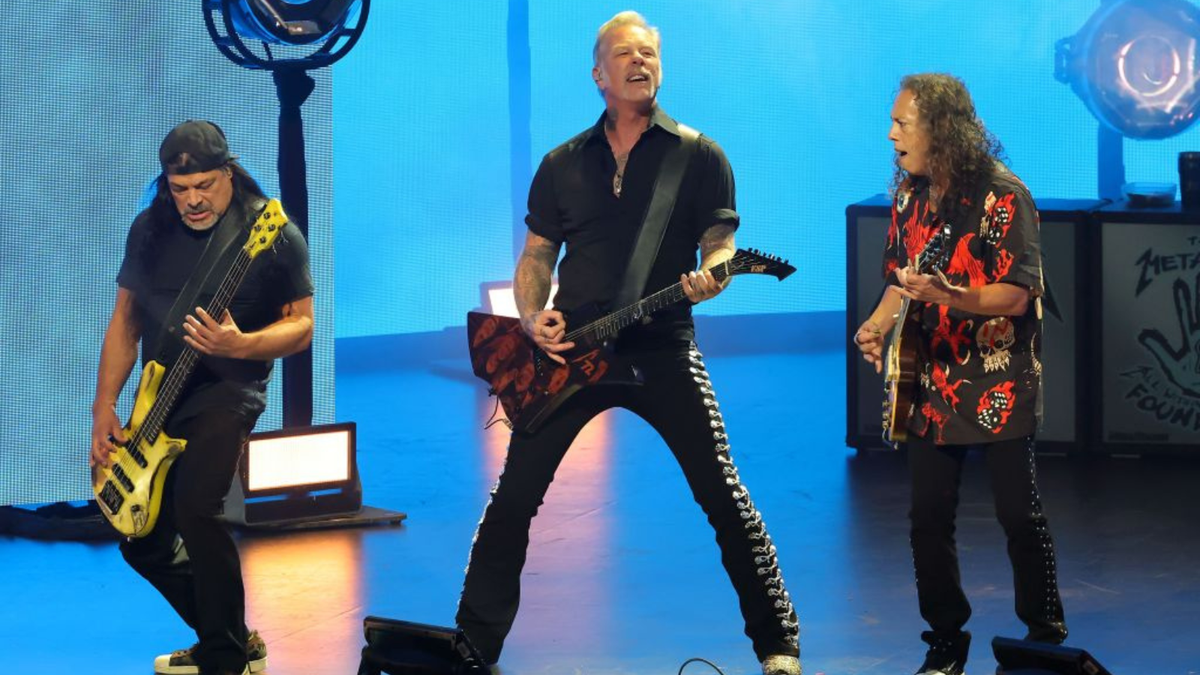

[Photo by Atiba Jefferson]

In early 2020 when they were working on Cavalcade, it “made sense to widen the spectrum of sounds,” he explains. “And I think that’s an important thing, because I say ‘claustrophobic’ about Schlagenheim, because there’s a lot happening. There’s a lot going on. It’s actually quite hard to pick out certain instruments. You might be able to hear something, but you won’t be able to figure out what it is that’s playing or making that sound. Whereas [on] Cavalcade, we made a very considered choice to make sure that the instruments sounded as natural as possible. And we’ve continued that with Hellfire as well.”

Even the artwork of Hellfire has the texture of infinity. The colors are all vibrant and bright, to an almost blinding extent; greens, yellows, reds all drip into a kind of frame around a delicate pink sky and body of water that are only distinguishable from one another because of the shades. It looks like a portal to another dimension, and in a way, it is: “Never adequate enough/Enough, enough, come in, come in/Thank you,” Greep says at the end of the tiring first track, not at all welcoming but weirdly enticing.

“Sugar/Tzu,” the following song, instantly maintains the eccentricity by kicking off with the ringing of a boxing bell and an announcer asking the audience if they’re ready for the “sporting event of the year.” Whereas Cavalcade’s storytelling was third person, Hellfire is first person, imbuing the experience with a new sense of personality and closeness. Greep becomes the characters, almost like he’s being possessed by the intensity of his own imagination. The biography refers to them as “players” and lists them out with peculiar details: The Captain (lives: underground, his instrument: any oenological accessory), The Defendant (age: ageless, his weapon: lust), Freddie Frost (age: is younger than life, older than death), Satan (enjoys: your weakness), just to name a few.

No matter how specific the storylines in the songs are, they are, at their core, a morbid lens into the darkness of life. Greep says most of the people depicted are scumbags. “Eat Men Eat” explores temptation in a Garden of Eden-esque way; “Welcome To Hell” dives into the viciousness of war, and doesn’t hold back from shedding light on the persuasive propaganda: “By standing in line today/You secure a place among the saints,” Greep sings against discordant rhythms. Picton claims, though, that there is a tenderness hidden within each song. Maybe it’s absurdist humor in “The Race Is About To Begin” when Greep says: “Idiots are infinite/And thinking men are numbered,” or the soft twang of “The Defence” buoyed by a jazz ambiance.

Hellfire began as soon as Cavalcade was unleashed into the world. “There’s just an unbelievable feeling once what you’ve finally been working on and been discussing for ages — with the intersecting elements of the marketing campaign, the promotional stuff, the cover, the music itself, the mixes — is out, and you don’t have to worry about any of that stuff at all ever again. It’s a very liberating feeling,” Greep says. “Once it’s actually out and done and finished, you can really just go into doing new stuff and act as if the thing you’ve been working on for so long doesn’t even exist, or has existed a long time ago. We don’t really like reveling in what we’ve done, what we’ve released. Once it’s out, at least for me, it’s a weight off the shoulders.”

This forward-moving approach undoubtedly contributes to what distinguishes black midi from other bands. Their sound is ever-changing, constantly being refreshed. Whereas many musicians go into making albums with the goal of either trying to surpass their last one or make a continuation, black midi disregard their past work altogether and aim for something new. And it shows in the music.

“As soon as the album came out, in May of last year, we started working tirelessly on a new thing because we had some songs, but it was only once [Cavalcade] was out that we fully committed to it,” Greep says. “In the week after it was out, straight away we go into the rehearsal room, playing together and working stuff out. I’d say within a month — within a few weeks — we basically had all the songs. It was just a matter of logistics, scheduling recording dates, but the songs are basically all there.”

[Photo by Atiba Jefferson]

The band are reluctant to give themselves credit for working at such a fast pace. Heading into the rehearsal space to jam out the day after releasing a record is second nature to them. “It’s not a case of principle; it’s not a case of doing it because we really want to do it and are rushed to put out another album,” he says. “The songs have just come pretty easily. It’s adapting the situation to how it’s going creatively. We never decide on putting out an album before all the songs are there. It’s just a case of all the tracks coming into place and working together well and then saying, ‘OK, it looks like we have an album here.’”

“We have this saying,” Picton jumps in, “which is, ‘There is no off-season.’ We’ll take a couple of months off or whatever, but even then you’re still doing loads of stuff, like writing songs at home or practicing.”

When Greep opens the record with the menacing declaration of “There’s always something,” it’s on the nose. There’s always something to be inconvenienced by, to be miserable about — but there is also always something to write songs about, to explore. The result is Hellfire, a bombastic, evocative inquiry into evil that uses dark comedy and disorientation to its advantage. It’s also a way of having fun. It’s not dogmatic; it doesn’t possess any sort of agenda, aside from the goal to entertain. Instead of answering questions, Greep poses them, like on the finale “27 Questions,” acting as Freddie Frost: “Do nuns fornicate?/And scientists pray?/Is a sin committed every moment of every day?”

There’s no answer — only chaos, as Frost blows up “to the size of a hot air balloon” and wheezes and moans in pain. “But we all just laughed at the sad, old oaf,” Greep sings, and then ends the album with, “And laughed all the way home.” black midi don’t take themselves too seriously, and that’s part of why everyone else takes them seriously. They know that there aren’t answers to most questions; they also know that the best way to go about the darkness of life is to laugh. In the midst of a pandemic, a repulsive political climate and a stream of never-ending bullshit, Hellfire is one big, retaliating laugh in the face of it all.

![All That Remains – Forever Cold [Official Lyric Video] All That Remains – Forever Cold [Official Lyric Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/U8D_WWkYDEw/maxresdefault.jpg)

![OneRepublic – Hurt (with Jelly Roll) [Official Music Video] OneRepublic – Hurt (with Jelly Roll) [Official Music Video]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/pDrD73iohmA/maxresdefault.jpg)