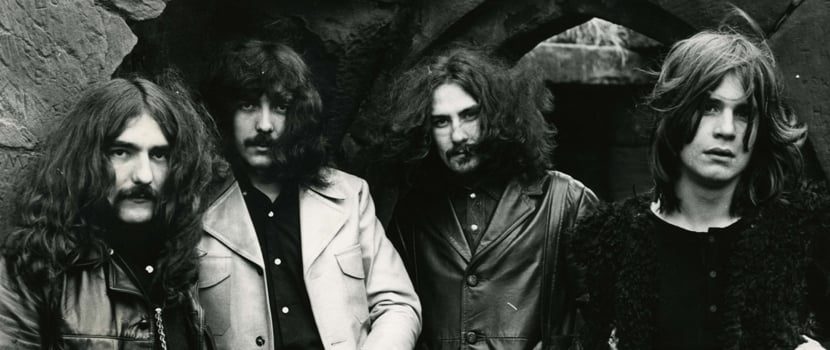

Slipknot appear on the cover of the Fall 2024 Issue — head to the AP Shop to grab a copy.

April 27, 2024: It’s been a long time since Slipknot felt this ferocious. Before the glow-stick Las Vegas skyline, nine boogeymen in red coveralls dart around the main stage of Sick New World Festival. Corey Taylor’s screams are tattered and raw, like his mask’s corpse skin and dangling dreadlocks. Guitarists Mick Thomson and Jim Root thrash and burn. DJ Sid Wilson — the gas mask guy — scratches into the chug. Pummeling his custom snare drums and kegs setup, Shawn “Clown” Crahan’s chop shop percussion weaves into the blast beats of the band’s primary drummer — an until-recently anonymous new member. Whoever he is, it’s working.

Of the nine musicians onstage, only the aforementioned five date back to Slipknot’s debut album, whose 25th birthday they’ve been celebrating all year. Since they emerged from the obscurity of Des Moines, Iowa, their demons followed close behind. But here they are, under the Vegas lights, where time blurs and youth feels eternal as long as the hits keep hitting. Whenever Taylor baits the crowd with a mention of 1999 — which is often — the response is rapturous. In contrast, nothing is offered from Slipknot’s most recent LP, released less than two years prior. Whatever warning rings for Slipknot’s long-term health is quickly squelched by quarter-century-old classics: the rap-metal whiplash of “Spit It Out,” the death tremor of “Surfacing.” The thousands-strong shout-along as Taylor eviscerates his absentee father on “Eyeless.”

Read more: “People like listening to me being horribly in pain”: the oral history of Korn

Slipknot is a 60-minute slaughterhouse. It’s some of the most extreme music ever to reach a mainstream audience. It rerouted the trajectory of metal and terrorized parents and school principals. It made Slipknot heroes to misfits who painted their nails black and brushed off digs from meathead jocks and shitty stepdads. “They could tell it was real. They could tell it came from a place that understood what it was like to be marginalized,” Taylor tells me, the venom palpable in his voice. “We were so fucking hungry we would have eaten through the backs of people’s heads.”

Lately, Taylor has been facing what’s long rattled inside his own. Back in January, the 50-year-old frontman canceled his upcoming North American solo tour, citing mental and physical health. After fans responded with a mix of disappointment and concern, Taylor released a worrisome, homemade video, shot from inside his car: “Over the last year, I have had a complete and utter breakdown of boundaries… Mental health, ego, entitlement… culminating in a very, very real, very near relapse.”

Taylor’s bleeding psyche is evident in his lyrics — for Slipknot, his other longtime rock band Stone Sour, his two recent solo albums, and his countless collaborations and side hustles. The video was especially stark.

“That’s exposing. He does it because there’s people who feel the same way he does,” Clown says. “They need him.” When I ask Root about the video, he adds another unfortunate truth. “As men, we won’t seek help until we’re on that ledge.”

In a therapy-styled 2017 video interview, Taylor revealed life-spanning trauma. He grew up in poverty and crisscrossed the country with his mother and sister while his mother looked for work. Maintaining friendships was difficult. When he was 10, he was raped by a 16-year-old boy he’d befriended after his family’s latest move. Threatened with violence by his abuser, Taylor didn’t discuss the incident for years. Later, when Taylor was 17, he nearly overdosed on cocaine and other drugs at a party and woke up in a dumpster. In another instance, following a crippling breakup, Taylor attempted to end his life by taking pills. A chance visit from his ex-girlfriend’s mother rescued him. On camera, he sobbed as he let it all out.

I ask Taylor about the initial response to the video. “A lot of people hit me up saying it helped them get themselves back into therapy, or to try therapy for the first time,” he says. “I wish I had a better happy ending to that video than I did. I didn’t end up addressing those things until this year. A lot of my issues come from being convinced that I’m right, even when I’m wrong.”

Taylor spent much of Slipknot’s early fame as a barely functioning alcoholic, numbing his depression with booze and self-destructive behavior. In 2003, he had to be pulled back from jumping off an eight-story balcony at an LA hotel. At the insistence of his then-fiancée Scarlett Stone, he got sober and rededicated himself to building a healthy life around his two children. After that marriage ended, he began drinking again for several years before giving up alcohol in 2010. (He now has three kids and is married to dancer-choreographer Alicia Dove.)

By the dawn of 2024, Taylor hit what he calls “a real dark point.” He prefers not to go into detail but gives me some background: “I found that my pursuit of work and all things ego was killing me. And nearly killed me. So I’ve reinvested my life to the point [where] I’m only going to work so much. I’ll never be gone from home for more than two-and-a-half weeks. I’m putting importance back on the things I really value. That is the greatest gift I could give myself and my family.”

The day we chat, a Slipknot tour is less than two weeks away, but it seems he’s already put his plan into motion. “[My family and I] just got back from vacation — it started in London and ended in Edinburgh. We spent a week there, ran all over the U.K. dressed like Harry Potter.”

Back in 1999, the world was very different. The music biz would have likely scoffed at a rock star canceling a profitable tour over mental health. The powers that be might have flat-out refused. This was an era when national tragedies like the Columbine High School massacre were widely blamed on things like violent video games and (allegedly) satanic metal bands. Slipknot themselves had to endure awkward questions from misguided journalists trying to make the tenuous connection between their sinister lyrics and real-life murder. It’s unsurprising Taylor kept so much to himself. He tells me hardly anyone had known what he revealed in that 2017 interview outside a handful of his bandmates. “People like Clown and Joey [Jordison] knew. I talked to Paul [Gray] about it. I’m not sure anybody else [knew], to be honest.”

Tragically, Taylor no longer has two of those friends to confide in.

Gray, who donned the pigface mask and bass guitar, died of a drug overdose in 2010 at age 38. In 2021, Jordison, one of the most innovative rock drummers of all time, died in his sleep at 46. Jordison’s death gutted the metal community. In 2016, three years after his dismissal, Jordison revealed he’d been suffering from acute transverse myelitis, a neurological disease that temporarily cost him the use of his left leg. In his final shows with Slipknot, he was carried to his drum kit. Slipknot said he was fired for other reasons, insinuating personal and creative differences.

Gray and Jordison were core songwriters since Slipknot’s inception, the driving force behind songs that still dominate their setlist. To some of Slipknot’s more vocal fans, the band died along with them.

“[When] Paul passed, that was extremely difficult. The band could have ended right there,” Clown says. “Then, things happen with Joey, and that’s our story. Not ready for the world to understand. The world doesn’t know all things. The world doesn’t need to know. That was extremely difficult. That was probably the hardest thing ever. And still is.”

Slipknot’s 25th recalls the band’s fiery, formative days. Home base: Des Moines, Iowa. The middle of the 1990s, the middle of the country. The days moved slow, and the scent of cow manure hardly left the air. Slipknot coalesced in 1995 around the best musicians in the local metal scene, with Clown, Gray, and Jordison at the creative core. “All of us were so used to having the middle finger thrown at us,” Jordison said in 2000, for Slipknot’s first Alternative Press cover story. “When we threw it back, we did so with 10 times the venom.”

First, they were all in masks. Then, coveralls. “I love fashion. I always wanted sizzle,” says Clown, the longtime mastermind of Slipknot’s aesthetic. Rock bands had dressed up and worn masks before, but Slipknot pushed further. “We wanted to subvert image, take prepackaged rebellion, and sell it back to you,” says Taylor, explaining the giant barcodes branding their coveralls. First a friend of the band, Taylor joined Slipknot in 1997, desperate for some meaning in his life. “We wanted something so visceral, you wouldn’t be able to dismiss it.”

People speak of early Slipknot shows like some primordial force humans hadn’t learned to contain. Taylor describes one gig he’s at first hesitant to detail: “Nine psychos with all our gear. The stage is bowing in the middle.”

The site was a 300-person club in Reno, Nevada. Or maybe Provo, Utah. It’s probably best he can’t remember. The venue miscalculated Slipknot’s growing appeal and its small army of musicians, building them a creaky, L-shaped stage out of plywood and particleboard. “In the middle of the show, one of the guys — I think it was Clown — jumped and went through the stage. It’s caving in. We’re in a fit of psychosis because we’re mad half the audience can’t see us. We decided, ‘Fuck you, we are going to destroy your stage.’ We started pummeling it with kegs, guitars, anything we could get our hands on. We created a hole in the middle, and then we set it on fire.” The band bolted, leaving most of their equipment behind. They burned that night’s royal blue coveralls, never to don the color again. Such was the scorched-earth ethos of pre-stardom Slipknot.

“We were all ready to destroy something beautiful. When you have that kind of severity in your art, the audience is going to feel it,” Taylor says.

In 1998, Slipknot signed to Roadrunner Records, then best known for iconic metal releases from bands like Obituary and Sepultura. They got Ross Robinson, the producer behind Korn and Limp Bizkit’s debuts, to helm their first full-length. They scored a spot on Ozzfest ’99, where Ozzy himself would often watch Slipknot’s set from the sound booth. Even if Slipknot were playing to front rows dominated by boomer Sabbath fans skeptical of their masks, turntables, and auxiliary percussionists, they reached the kids in the nosebleeds who sorely needed them.

Slipknot dropped June 29 while Ozzfest played Indianapolis. “We had an early set,” Clown recalls. “Joey and I got off the bus — I always carried Joey on my shoulders… We hear these people: ‘Joey! Clown!’ Way over on the fence are four kids. They know who we are. One of the kids had at least 10 piercings in his face. They were tatted. They were younger than me. They pulled out our CD: ‘We’ve been following you for a while. We ran to go buy the CDs, then we rushed here and caught your set. Can we get your autograph?’ Joey and I looked at each other in complete awe.”

As Slipknot sold and sold, Clown dubbed their fans the Maggots, inspired by how they fed off the band and swarmed en masse once the pits opened up. Slipknot was certified gold in January 2000 and platinum five months later — a first for Roadrunner Records. Lead single “Wait and Bleed” scored a Grammy nomination. The same year, Eminem and Elton John delivered their legendary “Stan” performance, and somewhere in that LA arena, Slipknot got to take it in. Maybe they were in the nosebleeds this time, but they’d crashed a party they never sought an invite to.

“We were at the tail-end of nü metal,” Taylor says, reflecting on one of music history’s most derided (and misunderstood) genres. “At first, we embraced it. In a lot of ways, nü metal was the new punk. We loved that things were so heavy, because they’d been so light for so long.” For a time, rapping amid breakdowns and double-bass felt fresh. But nü metal’s expiration date approached with the new millennium, and Slipknot knew it.

They followed their smash debut with an even nastier album. 2001’s Iowa opens with the ferocious blast beats of “People = Shit” and unfurls an extreme metal opus, free of commercial (or nü-metal) concessions. It went platinum in two months, anyway.

Slipknot built a career that thrived beyond nü metal’s mid-2000s nadir. 2004’s Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) and 2008’s All Hope Is Gone both went platinum, and standout tracks like “Duality” and “Psychosocial” remain setlist cornerstones. In 2012, Slipknot launched Knotfest, a traveling metal circus inspired by debaucherous European festivals as much as its obvious forerunner. (Ozzfest was taking years off by this point, and even merged with Knotfest in 2016 and 2017). But as the sales and Grammy noms rolled in, they became increasingly less recognizable from the band that tore up the heartland in 1999. Beyond the losses of Gray and Jordison, percussionist and backing vocalist Chris Fehn left in 2019. Keyboardist and sample-slinger Craig “133” Jones split in 2023. Their current lineup includes non-’99ers Alessandro Venturella on bass, Michael “Tortilla Man” Pfaff on auxiliary percussion, and Jones’ replacement, whose identity has not been revealed since joining in 2023.

The response to Slipknot’s most recent album, 2022’s The End, So Far, was mixed. Already dispersed across the country, the members were further isolated by COVID-19 lockdown. Root was openly critical of the early demos (“Oh fuck, this doesn’t sound like Slipknot,” he told Guitar World), and the end product lacks the venom of Slipknot’s iconic records. “There’s this thing where it’s like, ‘There it is. I hear it. It’s a Slipknot song,” Root tells me. “It’s been a while since I’ve felt that magic happen. If I’m honest, I don’t know that the last album had any of that magic on it.”

A funny thing happened while Slipknot searched for their soul: nü metal crawled out of the cultural dustbin. Some whispered of a nü-metal revival. To others, it was even… cool? Marc Jacobs launched its 2023 Heaven line at a secret Deftones show in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Rumor has it Rihanna is a huge ‘Knot fan. When I searched the hypebeast-friendly resale site Grailed, a 2001 Slipknot Iowa tee sold for $350. Clown and his wife, Chantel, sat in primo seats for Balenciaga’s Spring 2023 runway show in Manhattan, alongside Pharrell Williams and Chloë Sevigny. “I could really feel our inspiration there,” Clown tells me. “Demna [Balenciaga’s creative director] was at our very first show in London, in 1999. He grew up with the culture of Slipknot, the cut of Slipknot. Watching these [models] walk, they got hair like Corey’s. They’re wearing rubber bondage hoods, the holes cut out where they had braids or roped hair, just like we invented.”

But nü metal’s resurgence goes beyond fashionistas taking cues from A.J. Soprano’s wardrobe. Bands like Deftones, Korn, and, of course, Slipknot, still command mass appeal with ordinary people between both coasts, and beyond. “Nü metal” has been steadily rising on Google Trends since January 2021, and over the past 12 months, it’s higher than it’s ever been (since tracking began in 2004). It’s no surprise Sick New World tickets sell out almost instantly, and Knotfest has hit over a dozen countries in North America, South America, and Europe. But to avoid fading into legacy act complacency, Slipknot must harness this momentum and deliver on their next studio project.

On that note, they can’t stop raving about their new drummer. Slipknot unveiled Eloy Casagrande in Vegas this past April, the 33-year-old tornado-ing through his first Slipknot shows after 13 years behind the kit in Sepultura. “How is playing with Eloy? It’s a hundred thousand percent different,” says Root. Adds Taylor: “The great thing about Eloy’s drumming is there’s a real groove that lends itself to our music, which can be lost if things are played too fast or aggressively.”

Casagrande replaced Jay Weinberg, a drumming protegé tasked with filling Jordison’s shoes back in 2014. Weinberg, the son of longtime Bruce Springsteen drummer Max Weinberg, grew up loving Slipknot. His November 2023 dismissal caused a stir in the fan community. Slipknot called it a “creative decision;” Weinberg said he was “heartbroken and blindsided” to be dismissed via phone call. Listening to how Slipknot talk about Casagrande, it’s hard not to draw parallels to Jordison’s loose, freewheeling style. The comment sections of Slipknot’s Sick New World videos contain similar sentiment. Regardless of the band’s intentions, they’re hoping the swap injects new life into their songwriting.

“Eloy is such a natural writer. I think he’s going to take us to some places we haven’t been in a while,” Taylor says. “I’ve got a lot to say, and I’m looking forward to expounding on a lot of different things.” Root mentions they’ve tossed around some names of producers. Clown is amped for the first Casagrande-era jam seshes. “Somewhere between 2025 and mid-2026, there’s gonna be writing. I think it’s gonna be sooner than later. Maybe we’ll be in the studio in the later part of 2025. There’s no expectations. No one’s in a rush, but we’re not going to blow it off, either.” They’ve finally satisfied the lengthy Roadrunner deal they signed in the ’90s, making them free agents. Clown envisions multiple paths forward, including a new major-label deal or even self-releasing. “I won’t sign a seven-album deal. But could we do one-offs or two? I don’t know. Am I interested in doing it ourselves? Well, that’s a lot of fuckin’ work. Could we do it? Yeah. Could it be beneficial for the band? Of course. Is it going to be 10 times more work? Absolutely.”

“I’ve been waiting all day to say these fucking words: WE COME TO YOU LIVE FROM MADISON SQUARE GARDEN!”

Taylor, black “25” armband on his red jumpsuit sleeve, is having the time of his life. It’s Aug. 12, five shows into the Slipknot anniversary tour. Slipknot sold out the Garden, and they sound unstoppable. The crowd ranges from gray-haired dads in Slayer shirts to kids barely filling out their Slipknot replica coveralls. Not a note of music made after ’99 is played, but hardly anyone has dipped early, even as the closing notes of “Scissors” punctuate the night. Casagrande is going so hard that Pfaff just stands behind the massive drumkit and points. This is not a band that are ready to go away.

The ball is now in Slipknot’s court: Go write another classic. An album they can play from start to finish, like the one they’re touring right now. No, they can’t go back to Des Moines, Iowa in 1999. Taylor and Clown spend much of their time living under Pacific Time sunshine. The mental health journey is nonlinear and never-ending, but the band are doing their best to stay on it. If peace is worth striving for, then what’s lurking behind you in the shadows?

Clown thinks back to 1998, thundering down the Pacific Coast Highway, en route to record Slipknot in Malibu. “We were coming over the hill from Santa Monica down the ramp, looking at the Pacific. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky. The sun was sparkling off the water. It was too beautiful for what we were about to create.”