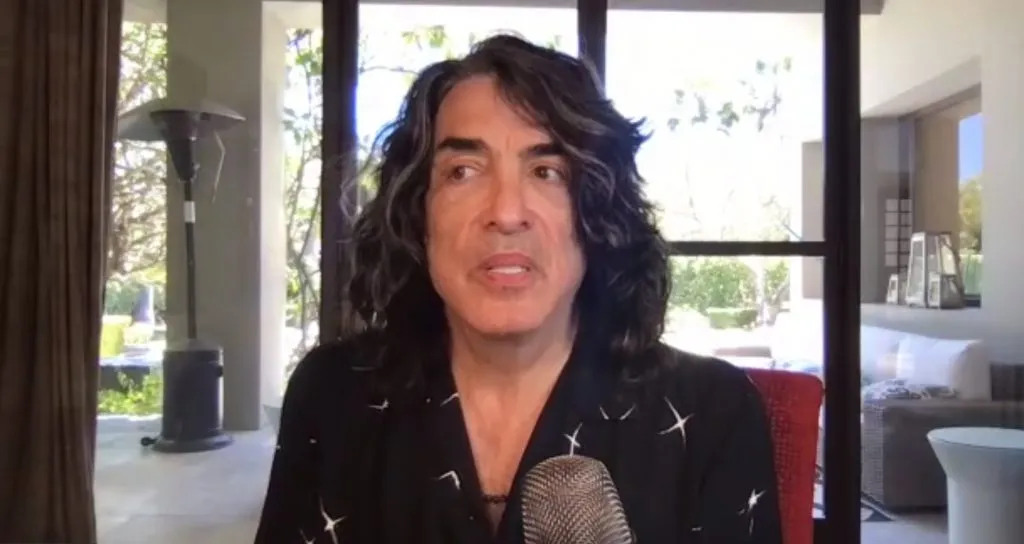

Anyone who thinks of the Cowsills solely as the eternally sunny harmonists behind ’60s hits such as “The Rain, The Park & Other Things” and “Indian Lake” (their 1969 version of “Hair” is a fried psychedelic masterpiece) or the brother/sister/mother band whose exploits inspired television’s The Partridge Family isn’t paying attention. Though Bob, Paul and Susan Cowsill are an annual part of the Happy Together Tour of fellow ’60s/’70s pop sensations, the trio has continued recording its own new material with albums such as 2022’s Rhythm Of The World and the newly released, 1998-recorded Global.

Susan Cowsill, too, has been as an avatar of Americana, covering a Sixto Rodriguez song for her first solo single in 1976, playing as part of the famed Continental Drifters in the ’80s and ’90s and releasing two country-rocking solo albums (Just Believe It and Lighthouse), so far, in the 2000s.

MAGNET caught up with Cowsill while she was preparing for dinner in her New Orleans home shared with husband/drummer Russ Broussard.

I’ve witnessed the marvel of the Cowsills many times on the Happy Together tour. Which of your two brothers is a cooler tourmate?

That’s hilarious. You either come from a small family or a large one and like to stir the pot. You never disclose a favorite. Both of my brothers are equally awesome—we’re a three-headed monster, or at least a three-headed creature of some sort … And Happy Together is the best day job a girl can ever have, so we always have fun doing that.

Despite your first fame as a Cowsill, I initially discovered you as part of the Continental Drifters, the countrified power-pop outfit you shared with (ex-hubsand) Peter Holsapple (dB’s), (sister-in-law) Vicki Peterson (Bangles) and Mark Walton (Dream Syndicate). Poke into your credits before that, and you sang with Dwight Twilley and Carlene Carter. All this makes you partially responsible for Americana. How did you come to country pop in the first place?

That’s quite an overview. The music rang true to me. My initial work with the Cowsills and the pop music of our generation was what I was listening to while growing up in Ohio. But I always listened to country. My mom loved it: Porter Waggoner, Glen Campbell. I actually didn’t start writing any of my own music until I joined the Continental Drifters when I was 34 years old, so I had time to absorb it all. I’m thinking that the combination of all of the musical food that I ate and drank contributed to the sound I created then and now. So be it. Funny trivia fact: The Cowsills—and me, in particular—gave Glen Campbell his Grammy for “By The Time I Get To Phoenix.” The whole family was at the podium, and my brother Paul was holding me up while I read, “And the winner is … Glen Campbell.” Plus, the Continental Drifters have reunions all the time, and there is a new compilation album of ours with new songs, White Noise & Lightning, which is also the name of a book coming out on us. And there’s a tribute album (We’re All Drifters: A Tribute To The Continental Drifters features Marshall Crenshaw, Caitlin Cary, Steve Wynn, Kim Richey, the Minus 5, Rosie Flores, Don Dixon, Garrison Starr and more) to us from some of our friends

Let’s go back even further: You sign your first solo deal with Warners in the mid-’70s, and your debut single is you covering Sixto Rodriguez’s “I Think Of You.” This is 40 years before his revival because of the Waiting For Sugarman documentary, and it places you even more squarely, and presciently, at the tip of country pop.

[Laughs] You give me more credit than I am due. Here’s how that happened: I had made a deal with my mom that I could become an emancipated minor if I could get a job. So, I did. And Warner Bros. was bringing me material, like Carole King’s “It Might As Well Rain Until September.” Other than that, the bounty of the music they were bringing me was pretty horrible. But one song stuck out from the crowd, and it was “I Think Of You.” I didn’t know who Sixto was. I didn’t realize that I was part of that Sugarman history until I saw the documentary. So that was a happy accident. Years later when he played the Barclays Center in New York, he asked my husband and I to open for him as a duo. I felt like Cinderella.

The history of Global is fascinating, as Doug Morris and his then-executive at Atlantic who tried to sign you (Marc Nathan) loved the album, but they wound up not signing the band when they realized it was “The Cowsills”—that wholesome family band from the ’60s. Which is a shame, as the music—very Los Angeles power pop with a Fleetwood Mac-ish rock feel—was perfect for that time.

When I hear Global now, I am amazed. I mean, we were all so young. Bob Cowsill knows all the details, as he shopped it back then. All I remember is that everyone said no. So many of the execs who tried to shop our records back then got doors slammed in their face. We were in Los Angeles, just being a rock band, which is how we rolled. Bob Cowsill is a great pop songwriter, but we had to play under anonymous names so that people wouldn’t know who we truly were. I remember that the Secrets was one of our made-up names for show, the secret being we were the Cowsills. We were absorbing everything around us then, because we were contemporary people, part of a generation that kept moving. So, Bob and his wife, Mary Jo, wrote the bounty of the songs on Global, as did our brother Paul. Bob writes stories about other things and other people—that’s not me. I always write from my experience, and these songs were observational as to what was going on then. Every time I listen to “She Said To Me,” I think about the blessing that is L.A. and riding the ride, from the ’60s to the ’70s at the Whisky A Go Go to the ‘80s with the Go-Go’s, the Bangles and X—new wave, punk rock and holy smokes, you know? We hung out. We were an L.A. band. I may have just been Susan Cowsill, but I was paying attention. When I sang “She Said To Me,” I was being as cool as Blondie. “Falling For You”? That’s me being my Susan Cowsill new-wave self. It tickles me to hear it now, because I’m 65 years old.

Global was recorded in 1998, but just released. Cocaine Drain was recorded in 1978, but your label, Omnivore, is releasing that soon-ish. How and why is it that you guys keep recording these albums, and they get lost until they are found again?

Without trying, nothing with the Cowsills is ever intentional. I’ll use that phrase “happy accident” again for everything that’s ever happened with us. Through Paul Revere and Bill Medley to Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman, the Cowsills’ career got resurrected due to the recent interest in the baby-boomer movement. We never say die, so we’re back working—touring and recording—and it’s all so unexpected and really lovely. So, we got an opportunity to release new music we were doing (Rhythm Of The World), and Omnivore was interested in old product as well. I mean, Cocaine Drain was something we did with Chuck Plotkin, Bruce Springsteen’s producer and engineer. Global is its own journey, what with lying dormant for so long, getting it out of hock and still sounding contemporary. So, now is the time of the Cowsills. That’s glorious, and we are eternally grateful.

—A.D. Amorosi