“‘Who won,’ I said, ‘the election?’”

So sang D. Boon on “I Felt Like A Gringo.” By the end of the day on November 6, the news was in, and time and space conspired to keep this writer from self-consoling with some Minutemen records. Fortunately, a still-extent trio was in town with its own comforts to offer. The Necks—pianist Chris Abrahams, double bassist Lloyd Swanton and drummer/percussionist Tony Buck—were in their second hometown of Berlin. (While everyone in the trio is Australian, Buck lives in Berlin, and Abrahams has spent a lot of time here.)

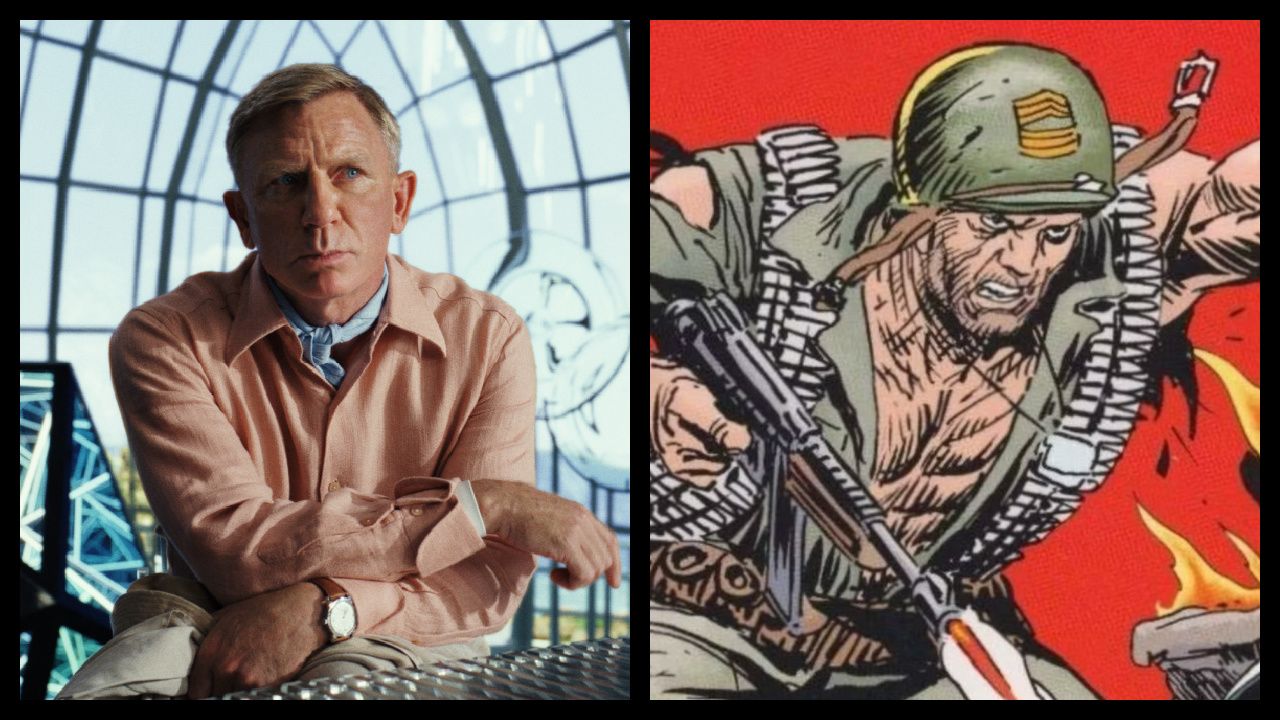

The three musicians were set up in the center of the Pierre Boulez Saal, an in-the-round concert hall built for classical music. It’s a dicey space for any band with a drum kit, but the Necks have been dealing with things as they come since the late 1980s, when they first convened in Sydney, Australia. From that point on, Necks concerts have typically adhered to a template that has an element of ritual about it. One of the members starts playing, and the other two respond. Together they improvise, ideally creating something greater than the sum of the three players’ contributions.

Abrahams began the first piece with a patient, consonant phrase—not quite a melody, at least not at first. Swanton put bow to strings, obtaining a slow, steady groan, and Buck drew a shimmer from his cymbals. Together, they seemed to be listening both to the room and each other, gradually adding elements until a layered mass of sound formed. Instrumental voices blurred together, then came into focus, then blurred again, as though the Necks’ collective mind was adjusting the laminal sound with a telephoto lens. It was beautiful, but perhaps due to the need to calibrate their attack to the hall’s acoustics, the Necks hovered but never quite lifted off.

Buck began the set with light, metallic taps and rustles, continuing the evening’s trend of moderate volume, but introducing more action. Swanton joined in with discontinuous patterns that turned Buck’s activity into a rhythm while Abrahams kept his hands off the keys, evidently listening to the sound move around him. Eventually he joined, first striking a single key, then building to two hands sustaining independent, repeating patterns. At that point, sounds began to emerge that couldn’t be attributed to any individual, but arose from the interaction between them. Liftoff accomplished.

From there, the music continued to transform and move, with streams of sound flowing with and against each other. When it finally touched back down, people exchanged knowing glances. The ritual had been enacted, and we all felt the change.

—Bill Meyer; photos by Pierre Boulez Saal/Peter Adamik